The move to remote work at the onset of the pandemic last year happened virtually overnight, with shelter-in-place orders forcing office workers to abandon the spaces where they spent most of their waking hours as if driven off by a nuclear meltdown. So people spent the next weeks and months reorganizing their lives and homes, carving offices out of bedroom corners and slipping in and out of home schooling sessions for kids between calls, with former commute hours now devoted to myriad other household tasks.

With the arrivals of vaccines and relaxed health protocols, some workers transitioned back to offices, albeit masked and distanced and part time. But with a statewide June 15 reopening date fast approaching, some companies are squeezing more workers to get back to their swivel chairs and microwaved office lunches.

But who has to come back to work — and when and where — is proving fraught as millions of workers face having a new way of living and working ripped away by managers requiring them to show up in person, or else. That tension could mean some workers leave for companies offering more flexibility and the ability to shed burdensome commutes in favor of time with family and friends.

Tech companies like search giant Google envision most employees coming into an office three days a week with some flexibility, and a percentage of workers staying remote for good. The company has previously said employees will stay at home until September but some can come in voluntarily before then.

Apple, which is planning to have employees return in September, recently took a slightly stricter approach, telling employees three days of in-person work would become standard in the fall, with a couple of weeks a year of pre-approved remote time also possible.

A small but growing group of Apple employees has reportedly pushed back against the requirements in an internal letter first reported by the Verge, raising questions of whether resistance to lassoing workers back to the office will grow in the tech sector, and beyond.

Darren Murph, head of remote working at software development tool maker GitLab, said the pushback was no surprise given the freedoms and flexibility a lot of people have gained in the last year.

“The friction that you feel is the transfer of power in a way that we have never seen in our lifetimes,” Murph said. GitLab has a mailing address in San Francisco but has been 100% remote since before the pandemic. Murph said workers pushing back against returning to in-person work after the pandemic largely proved offices don’t necessarily mean increased productivity.

“Layered on top of that is this universal awakening that the way we’ve always done things doesn’t necessarily have to be the way we do it going forward,” Murph said.

Pressuring employees to snap back to in-person work also raises the specter that they might just leave, especially in the case of highly skilled tech and other so-called “knowledge workers” whose jobs have moved online without much disruption.

“People who don’t want to come back raise their hands and look for another job,” said Grant McCraken, a cultural anthropologist who has taught at Harvard. He likened the situation to a “pro football team discovering that the New England Patriots are deciding to dissolve the team,” and swooping in to scoop up the scattering talent.

A mass exodus of workers from companies expecting their employees to soon return to the office hasn’t yet come to pass, with many still in the planning phases of installing people back into their cubicles. But with plenty of companies, like social media giants Twitter and Facebook, planning to allow long-term remote work for many, the prospect of jumping ship from a more rigid company may become more enticing.

Facebook said last month it would allow some employees to request permanant remote work, but switched gears Wednesday, telling employees it will open remote work to employees across the company as of June 15. The company said it plans to open most of it’s U.S. offices at 50% capacity by early September and expects a full reopening by October.

Even Salesforce, San Francisco’s largest private employer, plans to allow half, or more, of its employees to work from home for the long term, CEO Marc Benioff said in an interview this week. The company began allowing vaccinated employees back into its San Francisco headquarters in mid-May.

Salesforce, with its eponymous tower, and Airbnb have paid hundreds of millions of dollars to offload leases and other real estate obligations originally intended for office space they say they no longer need after the pandemic.

That raises the question of why some companies, like Apple, want workers to be mostly where managers can see them.

Apple did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

“Some would say, I think, that it was theater,” said McCracken, the cultural anthropologist. He said interviews and research he did with women working from home during the pandemic showed that the elimination of commutes and increases in time spent with family improved their well being without cutting into productivity at work

McCracken said some people he interviewed said “it feels like they’re putting their hand in my pocket, that they’re taking two hours from me that I had learned to use for myself” that would now flip back to wasted commute time.

Tech companies like Google and Apple are famous for their open floor plans and quirky spaces designed to encourage collaboration, and some companies have pointed to remote work as missing that personal spark that leads to the Next Big Idea.

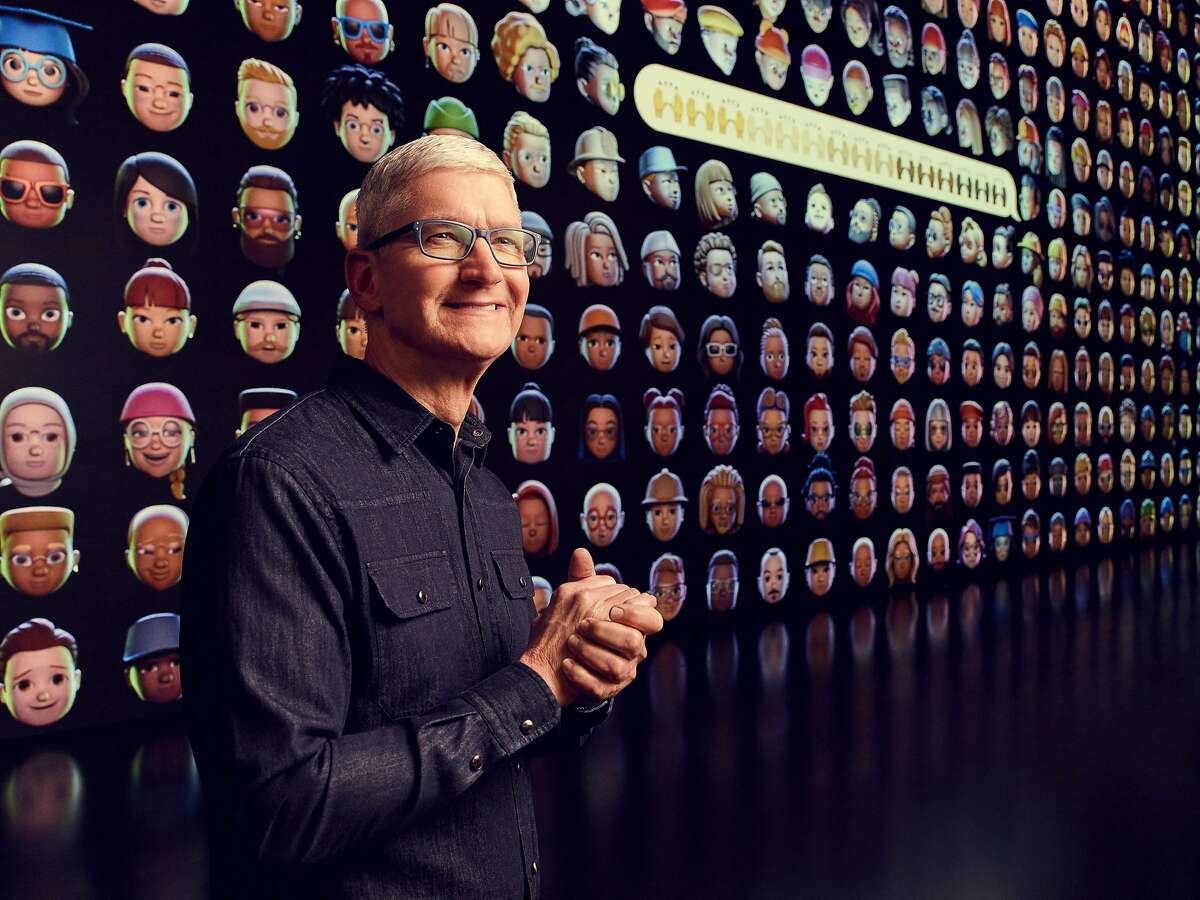

Apple CEO Tim Cook has said he believes in-person collaboration can yield results that remote working cannot. A group of Apple employees are pushing back against his demand for workers to return to the office.

Brooks Kraft/Apple Inc./AFP via Getty Images

Apple CEO Tim Cook wrote to employees in a recent letter, also reported by the Verge, that there were some things video calls cannot replicate about being together in-person.

Google has even redesigned some of its meeting spaces to allow for workers in the office to more easily connect via videoconference with those at home.

McCracken said that if the last year had proved anything, though, it was that huddling into a physical space, no matter how nice, doesn’t automatically mean connection and productivity.

“You don’t need to be siloed in the corporation with the people you work with every day to do that kind of creativity,” he said. “Maybe it’s better to let people out of the box.”

Murph, of GitLab, said the requirements to return could in some cases reflect managers’ lack of confidence in their abilities to lead or manage remotely.

Business leaders are “trying to go back into an incredibly costly, inanimate object that we just proved had little to no impact on productivity,” he said, referring to offices. “This is a global permission slip to do something different.”

Chase DiFeliciantonio is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: chase.difeliciantonio@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @ChaseDiFelice

from WordPress https://ift.tt/3zazudf

via IFTTT

0 Comments